This blog - Understanding the Tabla - attempts to initiate and, to some extent, explore the nuances of Tabla in a very lucid manner. It would help to put in perspective the theoretical, conceptual and practical aspects of the art and science of Tabla playing and some of the possibilities of incorporating Tabla into fusion music. It draws from the hands-on experiences of the author. Comments from pratictioners and music/tabla enthusiasts are sought.

IMPORTANT NOTE FOR STUDENTS OF TABLA

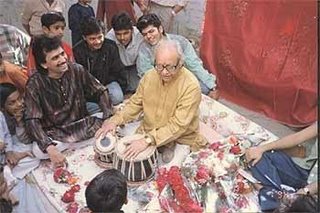

This blog in no way attempts to substitute or undermine the importance of tutelage from a Guru (teacher). Advanced knowledge on Tabla playing should be obtained from a Guru. To successfully navigate through the arduous roads of Tabla, the guidance and blessings of a Guru is paramount. In the picture, students are being blessed by teachings from Late Ustad Allah Rakha Khan - The Legendary Tabla Maestro, at my Guru Pandit Shri Divyang Vakil's residence.

A Guru, an exponent in the art & science of Tabla playing, builds up a strong technical and theoretical foundation in the Shishya (student), satisfies his curiosities, clarifies his doubts and makes the student capable of manifesting his creativity, thus making him capable to confidently take on the journey of Tabla. To make the most of the Guru-Shishya relationship, the Shishya should complement his Guru’s teachings with devoted Riyas (practice). The Riyas would largely involve playing the tabla, recitation of the compositions, contemplation, listening & observing other artists playing. The Guru is able to figure out the strengths and weakness of his Shishya and tailor the Riyas sessions to address those weaknesses.

Tabla – The Instrument

Tabla is the principal North Indian percussion instrument. It is extensively used as an accompaniment instrument for time-keeping and embellishment in various forms of Indian music viz. classical, semi-classical, folk, dance etc. Besides, over the years, it has also attained a coveted & revered status as a ‘solo’ instrument.

Tabla comprises of a pair of tuned drums to be played with both the hands. The pair of drums consists of a high-pitched, right hand drum, the dahina (also called dayan or tabla), and a low-pitched, left hand drum, the bayan. However, it is not a rule-of-thumb that the dahina must be played with the right hand and the bayan with the left. It depends on the tabla players basic instincts. There are quiet a few prominent tabla players who play the dahina with their left hand and the bayan with their right hand.

The dahina is responsible for many of the resonant & high-frequency sounds (or bols). It is tuned to a specific musical note. The tuning range of the dahina depends on its diameter. The tuning pitch is inversely related to the diameter, which may range from under 5 inches to over 6 inches (smaller the diameter, higher the pitch). Tuning the dahina is done by a hammer and is an art in itself which one learns by experience. A properly tuned tabla is a must for any accompaniment/solo rendition. The dahina is almost always made of wood (primarily saag wood or seasam wood)

The bayan provides the bass and is characterized by its swooping bass sounds that provide colorful embellishment. The body of the bayan is commonly made of brass with a nickel or chrome plate. Iron, aluminum, copper, clay or steel could also be used for the body of the bayan.

The combination of the two drums results into a vast repertoire of bol combinations and permutations.

Anatomy of Tabla

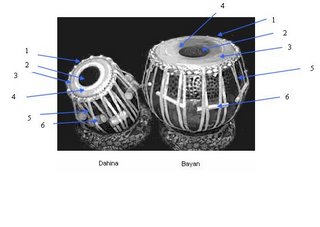

The picutre below identifies various parts of Tabla.

1) Pudi (the playing area)

2) Sayahi (the black area on the pudi)

3) Kinar/Chati (Rim)

4) Maidan (‘Ground’, area of the paudi excluding the Kinar and sayahi)

5) Vaghar/tasma (leather lace)

6) Gatta (wooden dowels to control the tension/pitch)

Evolution of Styles of Tabla Playing ("Gharanas")

Though percussion instruments similar to Tabla have been prevalent in India for thousands of years, the Tabla as we see today, has its roots in the royal courts of Delhi in the 17th and 18th centuries. Different styles/schools of tabla playing evolved over time and were named after the geography of their origin. They are known as ‘Gharanas’. The principle Gharanas are: Delhi, Ajrara, Farrukhabad, Lucknow, Benares, and Punjab. Although each of the gharanas has a distinct repertoire of compositions and musical knowledge, there are two major playing styles: Dilli and Purbi. The Dilli style derives its name from Delhi. It is characterized by a strong emphasis on rim strokes and use of the middle finger. The Purbi style derives its name from the Hindi word "purab". Purab means "Eastern" and reflects the fact that this style was popular in Lucknow, Benares, and other eastern parts of the country. The Purbi style is characterized by open hand strokes and a strong emphasis on material from pakhawaj (an ancient barrel shaped drum from which tabla was derived).

The origin of Gharanas can be largely attributed to geographic isolation due to lack of communication and transportation facilities in ancient times. Hence, in ancient times, exponents of a Gharana used to play compositions of their Gharana only and to some extent despised other Gharanas. However, in recent times (starting mid-twentieth century), with better communication and transportation facilities and an open approach, new generation tabla players (e.g: Ustad Zakir Hussain, Pandit Kumar Bose, Pandit Swapan Chaudhri, Pandit Anindo Chatterjee etc.) have become more versatile and freely use compositions from different Gharanas in their playing repertoire. Thus, the strict boundaries between Gharanas are getting blurred and there is an increasing trend towards convergence of various Gharanas

3 comments:

What is Taal??

The measure of time in music is called ‘Taal’ (or Rhythm). It gives a definite form to the infinite concept of time. Essentially, it divides time into regular intervals (Beats). The length of each interval governs the tempo/pace/rate of the rhythm.

Rhythm-the essence of life & music:

There is a definite rhythm in everything around us.

The earth’s revolution around the Sun (365 days), the changing of seasons, the functioning of biological systems (Heart Beats, breathing), each has its own rhythm. Besides, according to ancient scriptures, there is an underlying rhythm that governs the whole universe. Rhythm is thus the essence of life.

Disruption of rhythm leads to chaos.

E.g:

Prolonged unrhythmic striking of anvil or beating the drum is noise that’s more often disturbing and sometimes even deleterious to body and mind. On the contrary, the same striking or beating, when done rhythmically, becomes music and is pleasant to hear, having a positive effect on body and mind.

Disruption in the rhythm of heart beat could lead to death.

Just as in life, rhythm has an equally critical role in music and forms the core of any musical composition. The harmonization of Raag (=’a scale of musical notes’) and Rhythm is the mainstay of all forms of music.

Taal – A function of Beats & Tempo

Taal can be defined as a sequence of beats (matras) occurring at a regular tempo/speed (laya). It is a function of Beats & Tempo. [ Taal = f (Beat,Tempo)].

A matra is the fundamental unit of Taal. A group of matras form a ‘vibhag’ (analogous to the Western concept of measure or bar). The complete cycle of a taal is called ‘avartan’.

In a musical composition set to a specific Taal, the avartans are played in a cyclical manner (see figure 1). The first matra, SAM (meaning ‘with’, ‘together’ or ‘common’ in Sanskrit), indicates the beginning of each avartaan.

For e.g: If a Taal comprises of 8 beats, then these beats are played at a regular tempo in the following sequence: 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-1-2-….

Some of the commonly played Taals, their matras, vibhags and no of matras in each vibhag are:

Teentaal/Tritaal: 16, 4 (4-4-4-4)

Rupak: 7,3 (3-2-2)

Jaaptaal: 10, 4 (2-3-2-3)

Ektaal: 12, 2 (2-2-2-2-2-2)

Deepchandi: 14, 4 (3-4-3-4)

Beat/Bol:

Each beat in a taal is identified by a ‘Bol’. E.g: Dha, Ta, Tin etc.

In other words, Matras and Laya provide a structure to a Taal and Bols add meat and flesh to the structure.

Tempo:

Three fundamental tempos in music are:

1. Slow (Vilambit),

2. Medium (Madhya),

3. Fast (Dhrut)

They are in the ratio: 1:2:4

Thus, when one beat is played in one beat, it is Slow tempo, when two beats are played in one beat, it is Medium Tempo and when four beats are played in one beat, it is Fast Tempo.

Post a Comment